on grieving through objects

the (in)tangibility of loss

preface 1

I have been putting off this piece, and not because it means exploring my grief. At times, I dream of roaming in my grief through the rest of winter. Freely grieving all day, every day. I would pause the world around me, lay in a faraway place under a warmer sky, and get to know my grief without noise.

I would ask my grief how it decides to show up loudly one day and gently the next; I would ask why I cry in spells, for days and then not at all, and sometimes without a trigger; I would ask how I’m supposed to hold it.

Instead, I have been putting off this piece because there is so much of my grief that I have yet to get to know. The world around me does not slow down, but even if it did, even if I retreated in a warm, faraway place, I’d likely never reach complete knowing.

With that, I’ve decided that knowing is not a prerequisite to sharing. My grief is felt, whether I obsessively study it or not. Whether I actively, attentively sit with it or not. This piece is only a portrait. A portrait of grief, objects, my grandpa.

preface 2

My earliest memories revolve around materiality. Clinging to physical objects as a means of feeling, thinking, and imagining.

I’d turn to my dollhouse for regular escape, experimenting with ways to arrange the furniture, dress dolls, switch things around again and again. I was too focused on this adventure — the “setting up,” the creation of a material world — to play out dramas or make much “happen” for my dolls.

I’d watch HGTV alongside my mom, eyes glued to the TV, entranced by how Candice Olson and Genevieve Gorder made dreams come true through wall colors and textiles alone.

I’d dress myself in monochromatic outfits with a matching stuffed animal. Today, I am blue, and everything I wear is blue, I am everything I wear.

Vignettes like these affirm that I have always known the power of material belongings. The objects that define and adorn our homes, wardrobes, rituals, lives — everything that we touch like we mean it — are containers of identity, of stories. A phenomenon that is fascinating to study but does not need studying to be true.

concrete, intangible

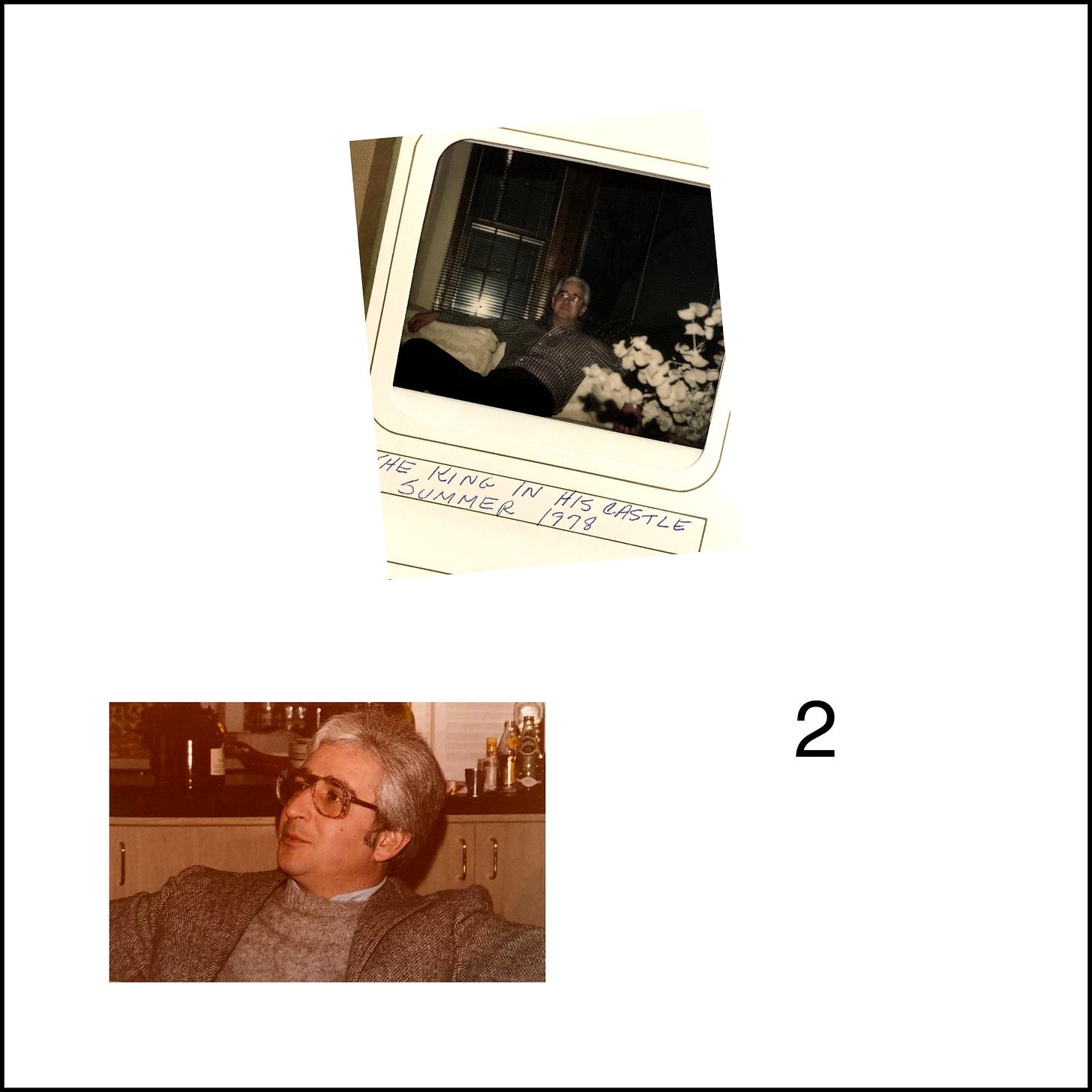

More than two months have passed since my dear grandpa died, my first major loss, the official end of his life, the official beginning of my grief. I miss everything concrete about his presence: The loss of our visits, our talks, his voice, his smell, his iconic, repetitive outfits, his tall stature. But I mainly miss everything intangible about him: His thoughts, his wisdom, his humor, his love, my love for him, knowing he is only a phone call away, our friendship.

The latter collection of losses forms a unique, difficult-to-pinpoint void. When I lost him, I lost the visits, and the visits ended. When I lost him, I lost his voice, and his voice was gone. But when I lost him, I wondered if the intangibilities might somehow linger. If I’d still be able to hear his thoughts and absorb his wisdom. If he’d still make me laugh.

What I’ve learned since losing him is that they do linger. They are ever-accessible via concrete, tangible things. He lingers in his left-behind belongings, in photos of him, in the ink when I journal about him, in objects I encounter that remind me of him, in my words when I speak out loud to and about him. He lingers in it all, but while the concreteness preserves his presence in some sense, it also reminds me that he’s gone. Keeps him here and surfaces my grief at once.

Here are some concrete things that have asked me how my grief and I are doing.

hospice house

He left in a place that hosts the dying process with profound warmth. The warmth of the care he received was reinforced by soft, golden yellows everywhere — yellow tile, yellow linens, yellow light. Warmth reinforced by a lively fireplace. Warmth reinforced by the generously-set thermostat against the cold, dark winter outside. The deepest privilege to pass surrounded by such warmth (him), and the deepest privilege to feel my heart break surrounded by such warmth (me).

glasses

His oversized glasses were always so dirty, smudged lenses. During his final moments, eyes closed and glasses-free, the frames sat on a table across the room, and their lived-in blur felt so alive, in stark contrast to his body.

hat, scalp

He carried such a distinct smell, especially his scalp. My scalp smells similar. I could not stop smelling his baseball hat during those days in hospice, which accompanied his glasses on the table across the room and locked in his so-him scent. I still smell the hat. I wonder if it will hold onto the scent forever. I rejoice in having my own scalp’s identical aroma to turn to if not.

coat

His winter coat hung on its designated hook when I entered his home after it was over. It was a nightmare to witness, walk in and see the coat as he had left it. I crawled into its fabric, wrapped myself in it. The coat still sits on the hook, and the hat hangs on top. I nearly cry each time I pass this scene. The coat and the hat on the hook. His uniform for going out into the world, ready to go on a hook, and he isn’t here to reap the convenience.

seat

He liked to sit in the same seat all the time. Maybe he needed to do this more than he liked to do it (schtick). In his kitchen, his sacred seat was a white leather barstool at the counter. The leftmost barstool in a row of four. Its upholstery is completely torn around the edges, while the other three barstools boast perfect condition. He was unintentionally rough on this poor barstool and it makes me smile. I have not been able to notice the extent of its tears until now because he was always in it. It’s so empty now. I will continue to visualize him there, or sit in it and settle into its tears to channel him.

voicemails

He was always checking in on the family, and because we couldn’t always pick up the phone, we are collectively left with a trove of voicemails. We have played the best ones back again and again. At hospice, at the cemetery, on his birthday when he would have turned 81. I have not listened to his voicemails or other recordings by myself. It feels too difficult to hear his voice all alone. I might spiral.

The sound. A vivid, full-bodied sound. I was so lucky to feel used to it. His Chicago accent, the declaration in his tone.

The words. By the time I was born, he was unafraid to use his full voice. That was how he embodied what it means to be your own person, wholeheartedly and unapologetically. He spoke his own language, collaging gibberish, Yiddish, profanity, bird noises, the occasional song, and miscellaneous nonsense. It all offered a glimpse into his mystical and distinctive inner world. And he would use his voice to show love, and relay unbelievable messages. Everything he uttered was striking in some way. Professing things like “Never let the incompetent possess your space” or “The beautiful thing is that I’m your mother’s father and you’re your mother’s daughter and it has all worked out” out of absolutely nowhere.

closing

The way the torn-up white leather seat makes me feel when I sit in it tomorrow might be different from the way it makes me feel when I sit in it the following day, following month, following year. Some days I won’t sit and I will just look.

While these objects might keep his essence frozen in time, they are dynamic — moving me along in my grief each time I face them.

The Words!!

We shouldn't just use the standard socially agreed upon way of communicating. It's so boring, so vanilla, so not individual.

Your sharing him here as you process the grief is immediately inspiring; both him in his full ability to use his voice, and you inspired by that to follow suit and be writing these words. It all then inspires me, the reader, to be less afraid of using every word, song, sound, noise, or language, that I know to communicate fully, Me!

Thank you for sharing. 🙏

eva this is so so beautiful </3 thank you for sharing